This is a transcript of a practice talk I gave for my Ph.D. qualifying exam. I’ve left in a lot of the mistakes to give it some character, and to learn a bit about how I talk. It’s also available in different formats here.

Ok, today I’m going to talk about automatic type annotations, and this is part of my PhD qualifying exam.

But first, I’d like to start with a story about annotating, from the real world.

So, there’s this company called LucidChart. They have a large JavaScript codebase, 600 thousand lines of annotated JavaScript, and they want to move to another language, TypeScript. It’s like JavaScript, but has static type checking.

But they have one problem—well they have two problems. One is that there’s 600 thousand lines of code to port, and the other is that this is an actively developed app, so they need to choose carefully about how they perform this migration.

So, they identified two options.

One is “gradually” typing it, which is very much what the phrase Gradual Typing is meant to imply: that you gradually port particular modules until you’ve finished.

It turns out there are over 2,000 modules, and this will take years, while trying to avoid stepping on any feet.

They identified another option, which was to stop the world, stop everyone from developing the app, and just sprint to the finish line.

What’s so interesting about this particular story is that they chose option 2 — they found a window, in fact it was their 48 hour hackathon, where no devs were working on the app for 48 hours.

So, six of the developers formed a team to perform this particular migration during the hackathon.

And, they tried to enlist their CTO, but he wasn’t as enthusiastic—he gives them a zero percent chance of this actually working. But six of them tried to do it anyway.

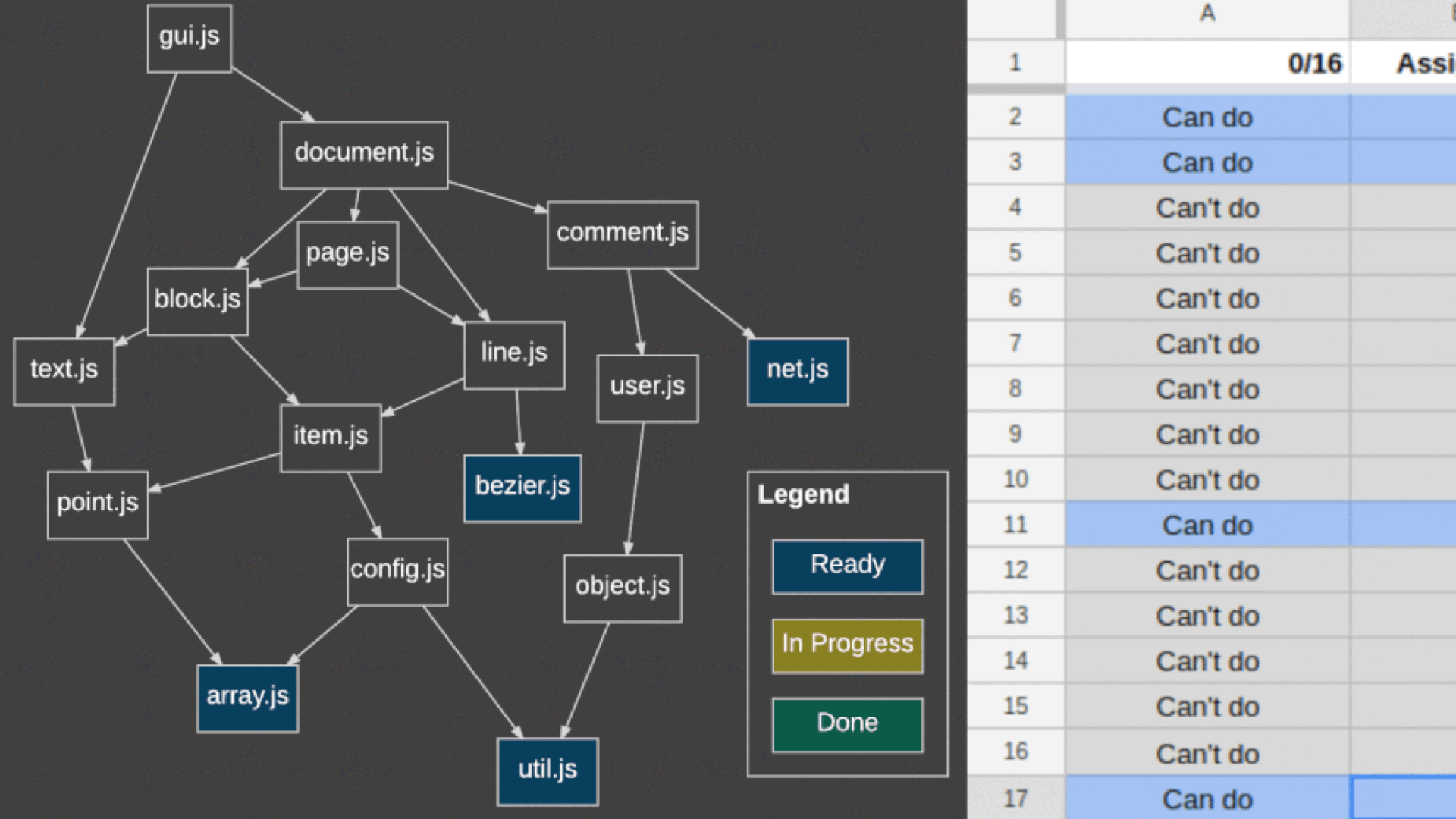

So, one problem is how to coordinate this between the six people. Well, they built a dependency graph of their JavaScript modules, and started from the bottom, using a 2800 line Google Sheet to coordinate which file they could port.

But! They have 2800 files in 48 hours—that’s about 1 file per minute. How did they do this?

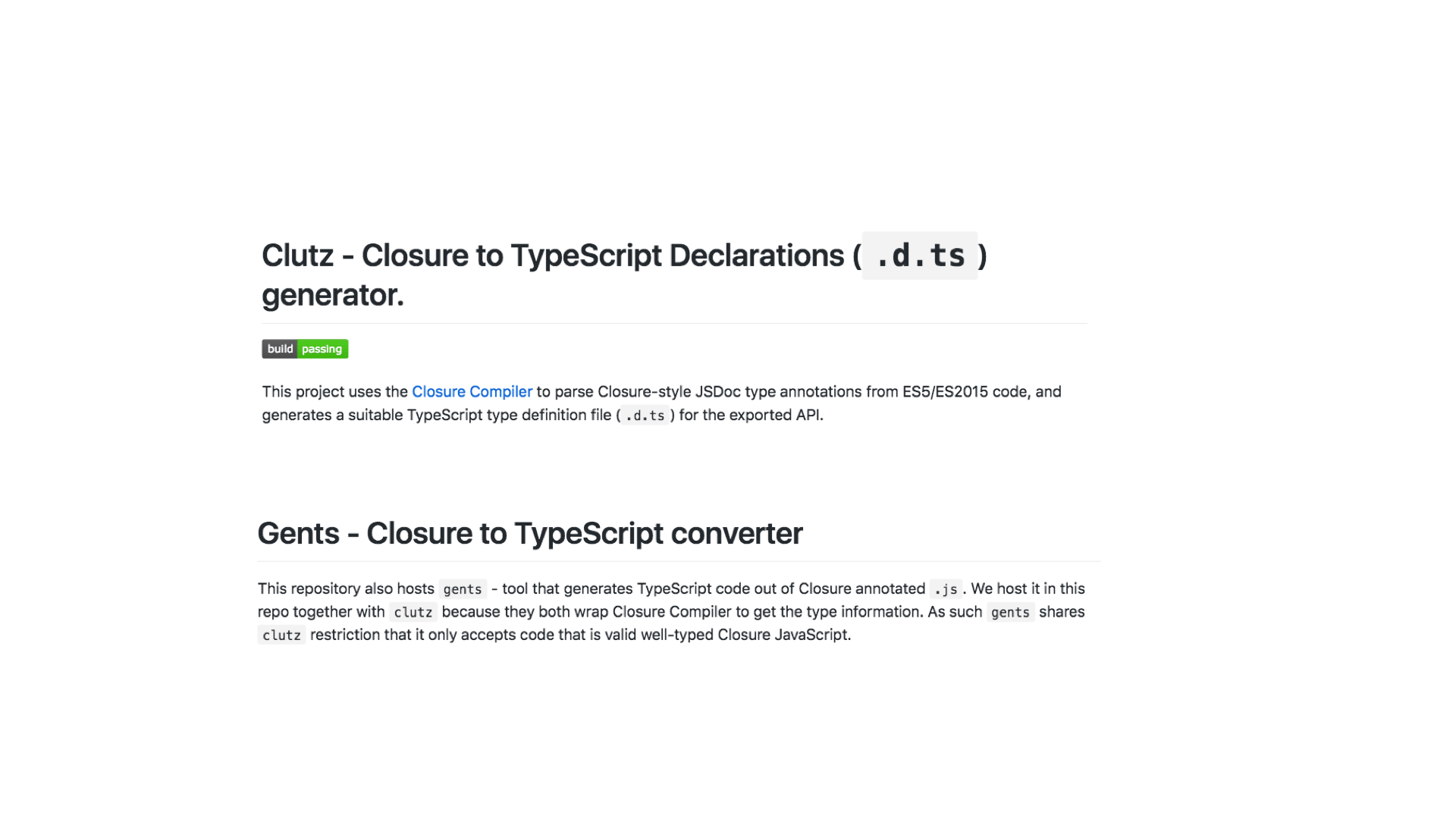

Well, their secret was to use partial automation—they used tools to port from their Google Closure-annotated JavaScript to TypeScript. And here are a couple of them.

So, in fact this was a happy ending for LucidChart. They converted their 600 thousand lines of annotated JavaScript to 500 thousand lines of TypeScript. And they did this using partial automation.

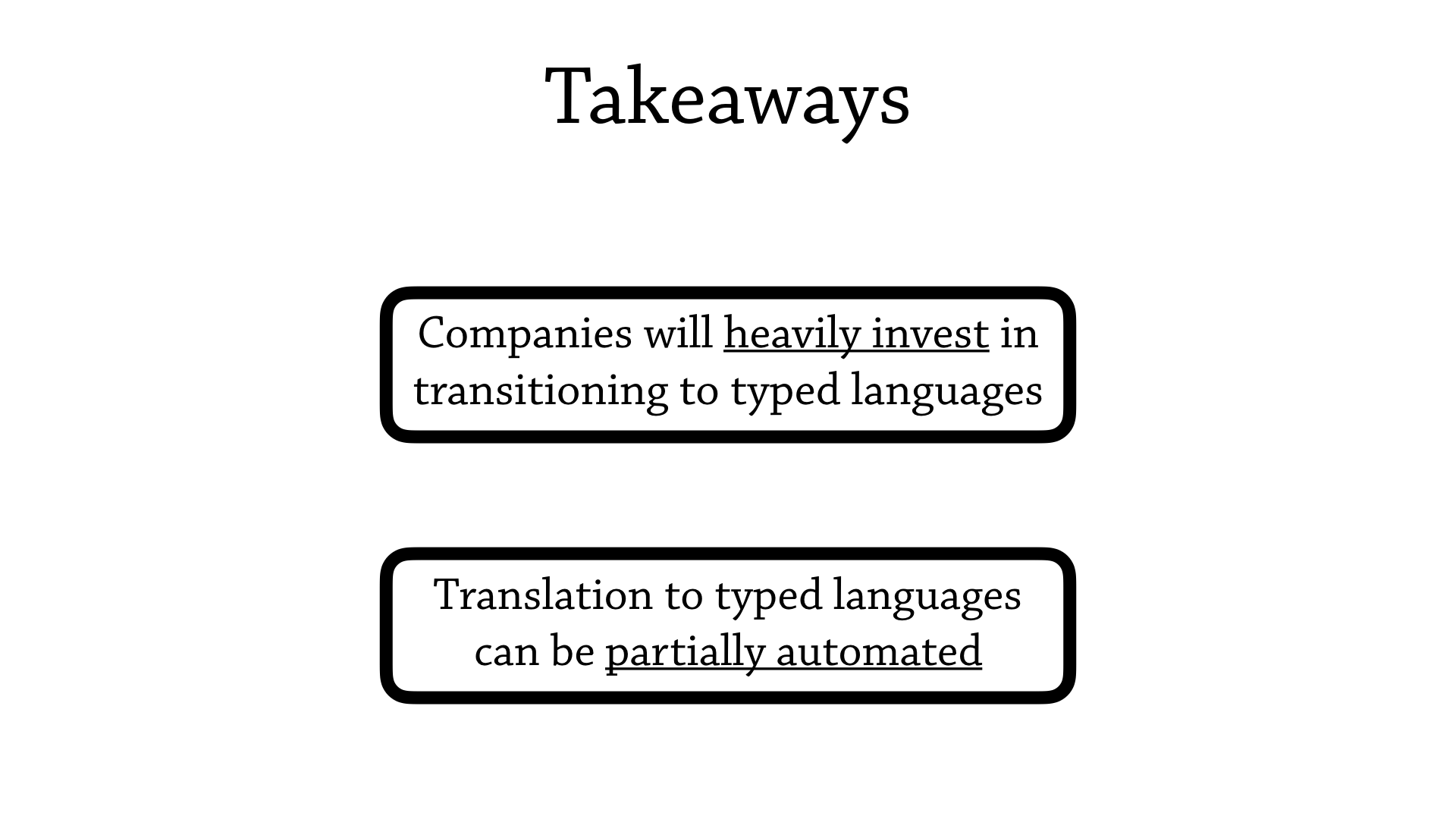

This is great for LucidChart, but what can we take away from this particular story?

Well, myself, I’m taking away that companies heavily invest in transitioning to typed languages, and they enjoy their benefits over untyped languages, like static error messages.

And, my biggest takeaway is that translation to typed languages can be partially automated—and this is really relevant to the fields of optional typing and gradual typing: there’s a lot of languages that are coming out that sell that you “just need to annotate your code, and you have magically converted your untyped code to be typed, or to be contracted”, but we disregard the effort needed to actually perform this migration.

Ok, so that’s the end of that story. Let’s start trying to motivate some of where my research comes from.

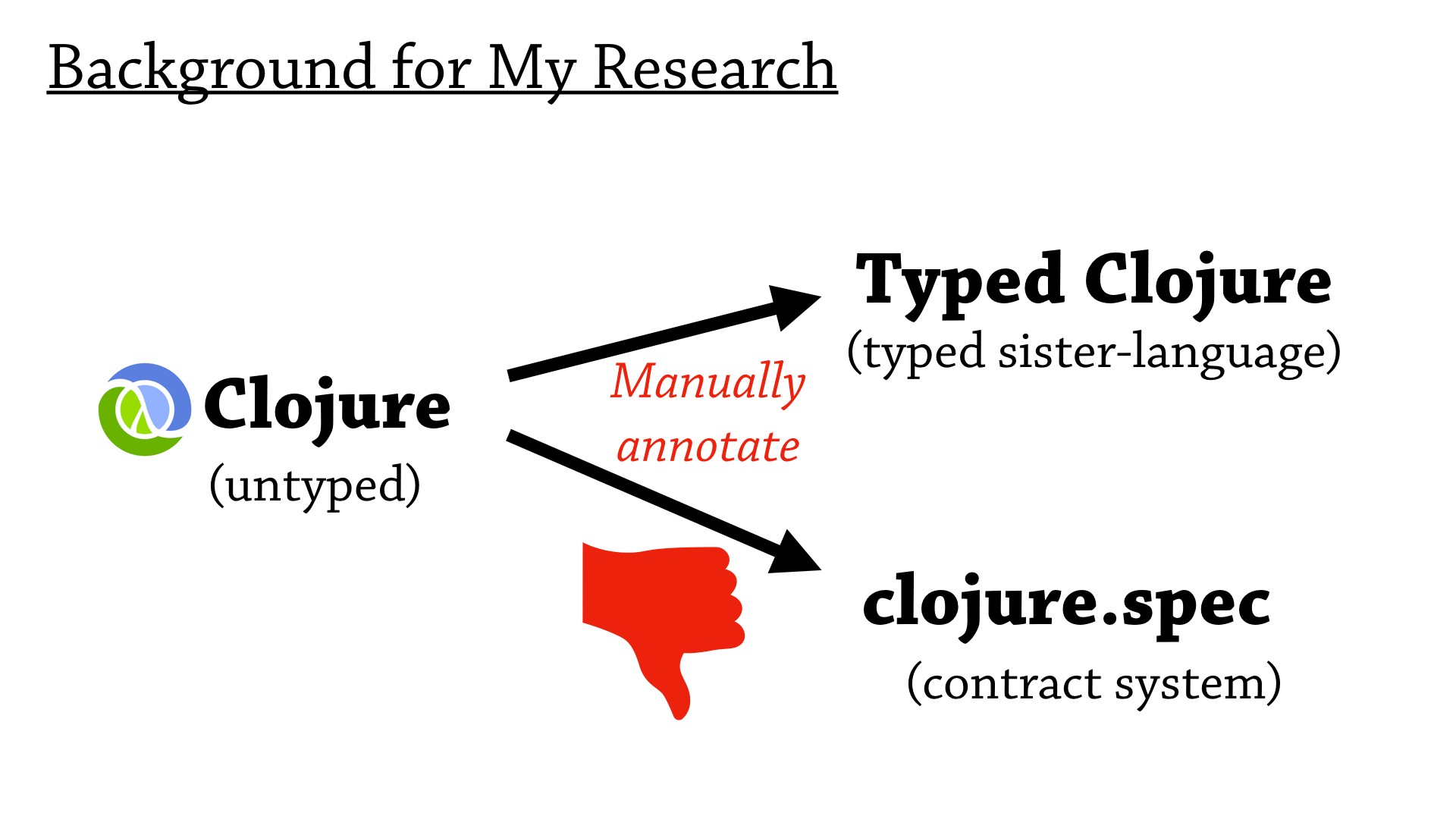

So I work in a programming language called Clojure—it’s an untyped Lisp, on the JVM. And, at the moment, I’m interested in the translation of, the manual translation, of Clojure to Typed Clojure and clojure.spec. So Typed Clojure is a typed sister language, it’s basically a static type system for Clojure; and Clojure.spec is a contract system for Clojure.

And, my observations are that this manual annotation just takes too much work, and discourages people from using these tools in the first place.

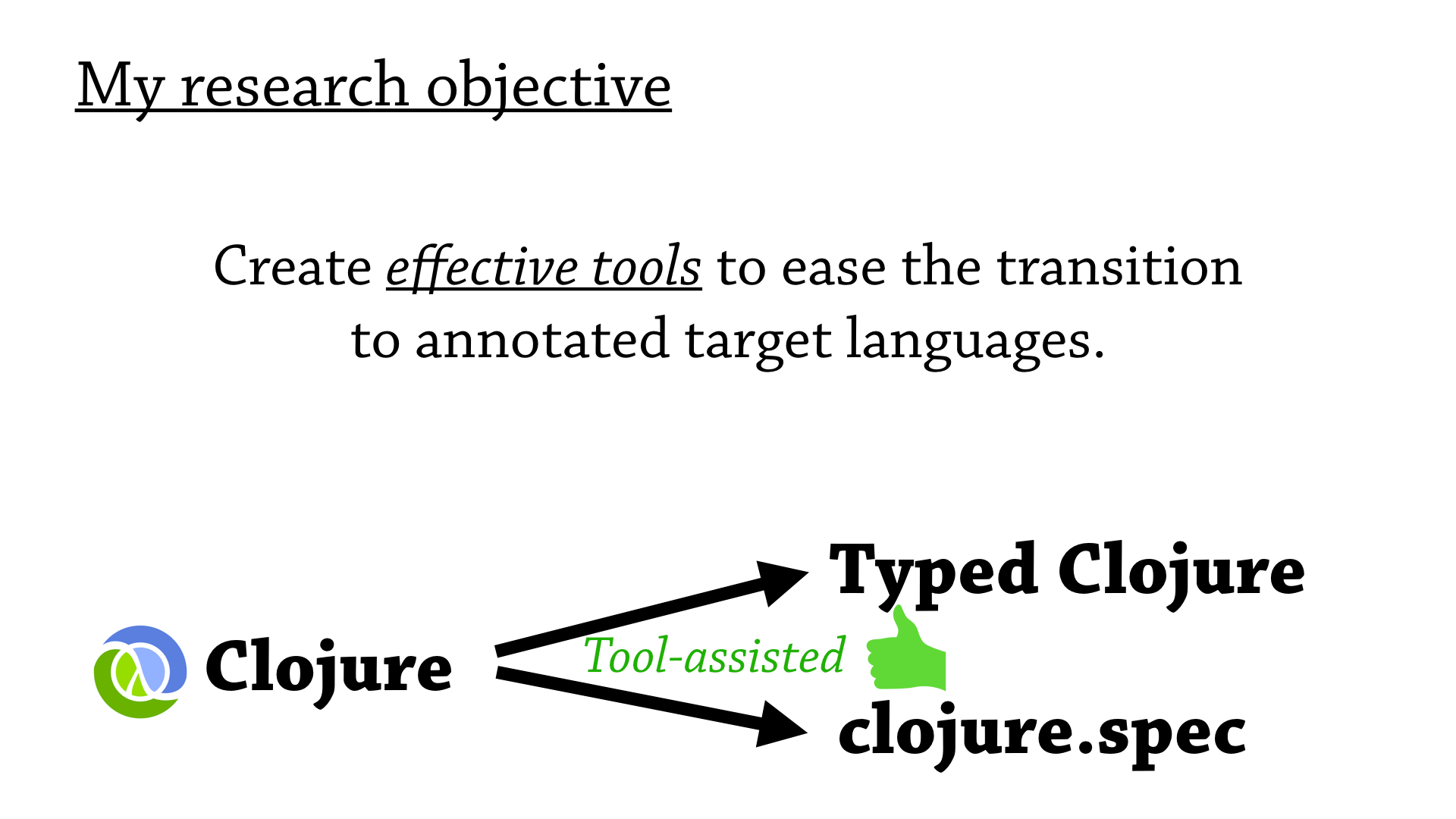

So my current research objective is to create effective tools to ease this transition to annotated target languages—so when we go to from Clojure to Typed Clojure, we can do this in a partially automated way, with a tool.

And, breaking down my approach about how I do this, I first understand the theory of the target language—that is the language that we’re translating to—then I understand how it’s used in the real world, and then I use that information to create a prototype tool and then iterate on that tool by comparing to similar tools in the wild.

Ok. This particular talk is a quals presentation, so what I’m going to do, I’m going to use this framework of theory, practice, and comparisons, and thread the quals questions through these sections, and then take questions in between each quals question.

Ok. So the first section—I say, that to create effective tools to translate to annotated languages, you need to understand the theory underlying that annotated language.

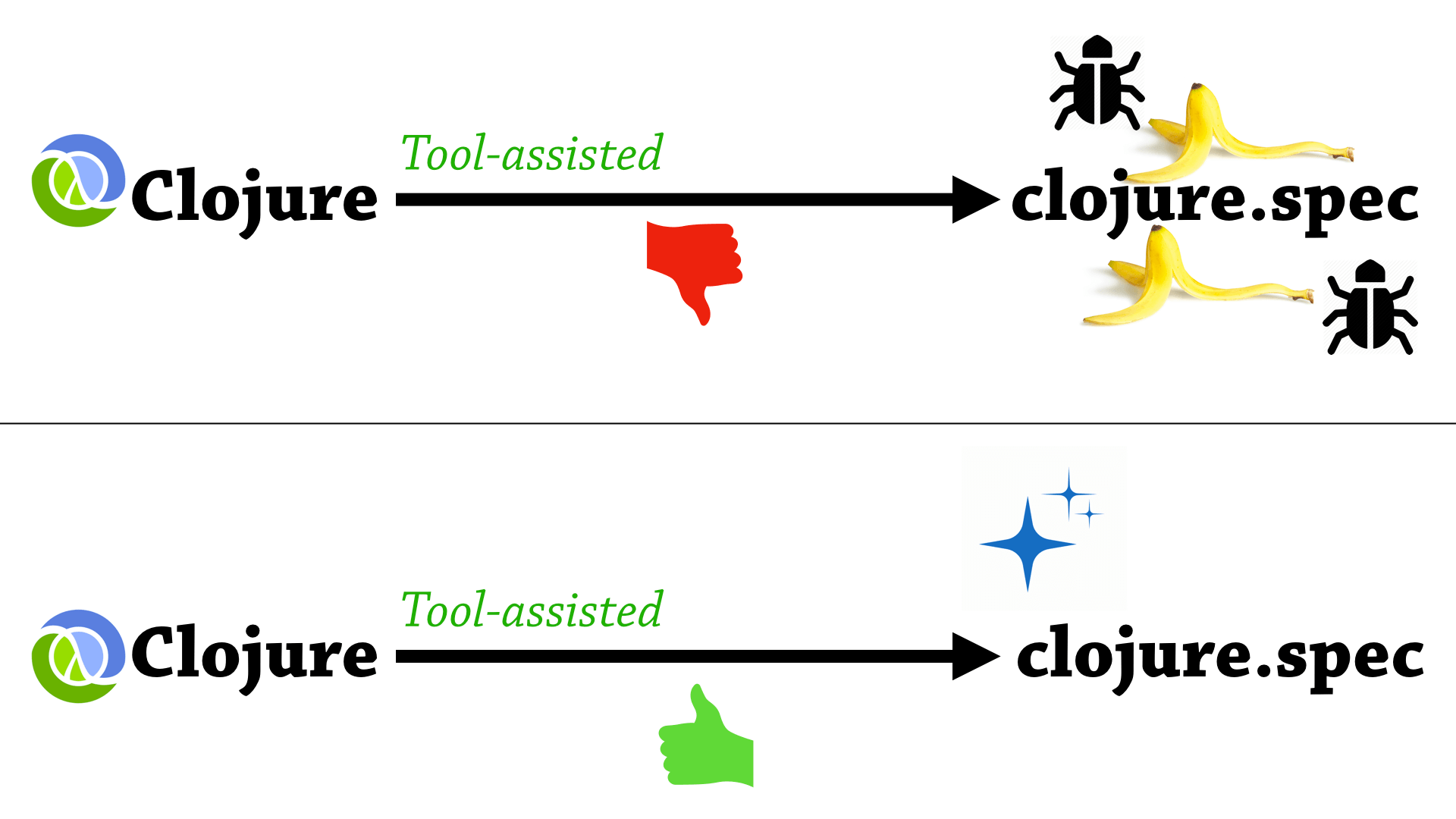

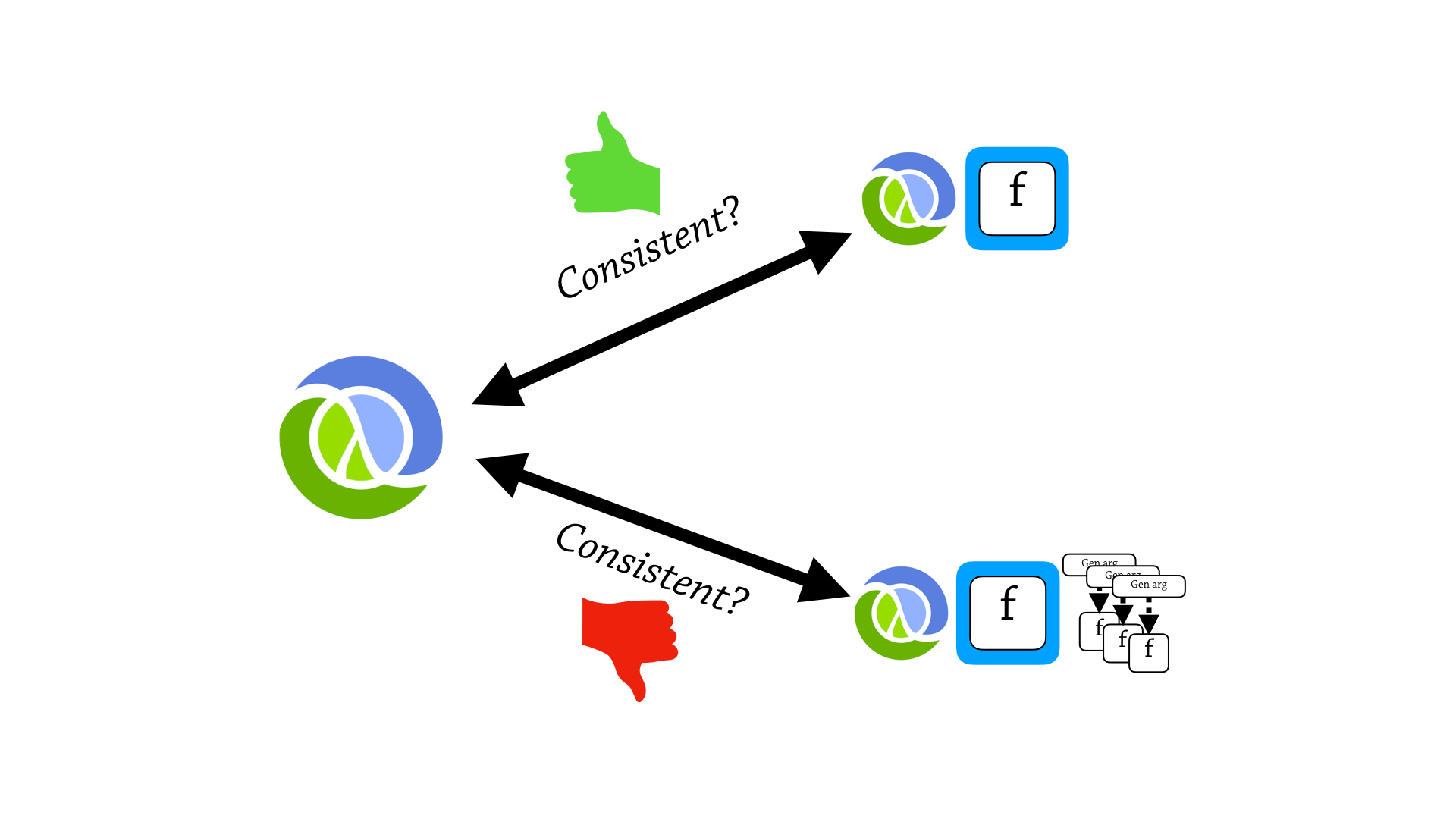

So why do we care about this at all? Well, as you can see in this slide, there are two situations you can get in when you automatically generate annotations.

So, the bottom situation is a squeaky clean situation, and the top situation is not quite as good. So, let’s look at the top situation.

We start with Clojure, we apply our tool, and then we get out a buggy mess, with lots of banana peels and traps in our annotations. Now, how can an annotation have traps and bugs? Well, with clojure.spec, it kind of gets interesting, so that’s where I’m going to go in this part of the talk.

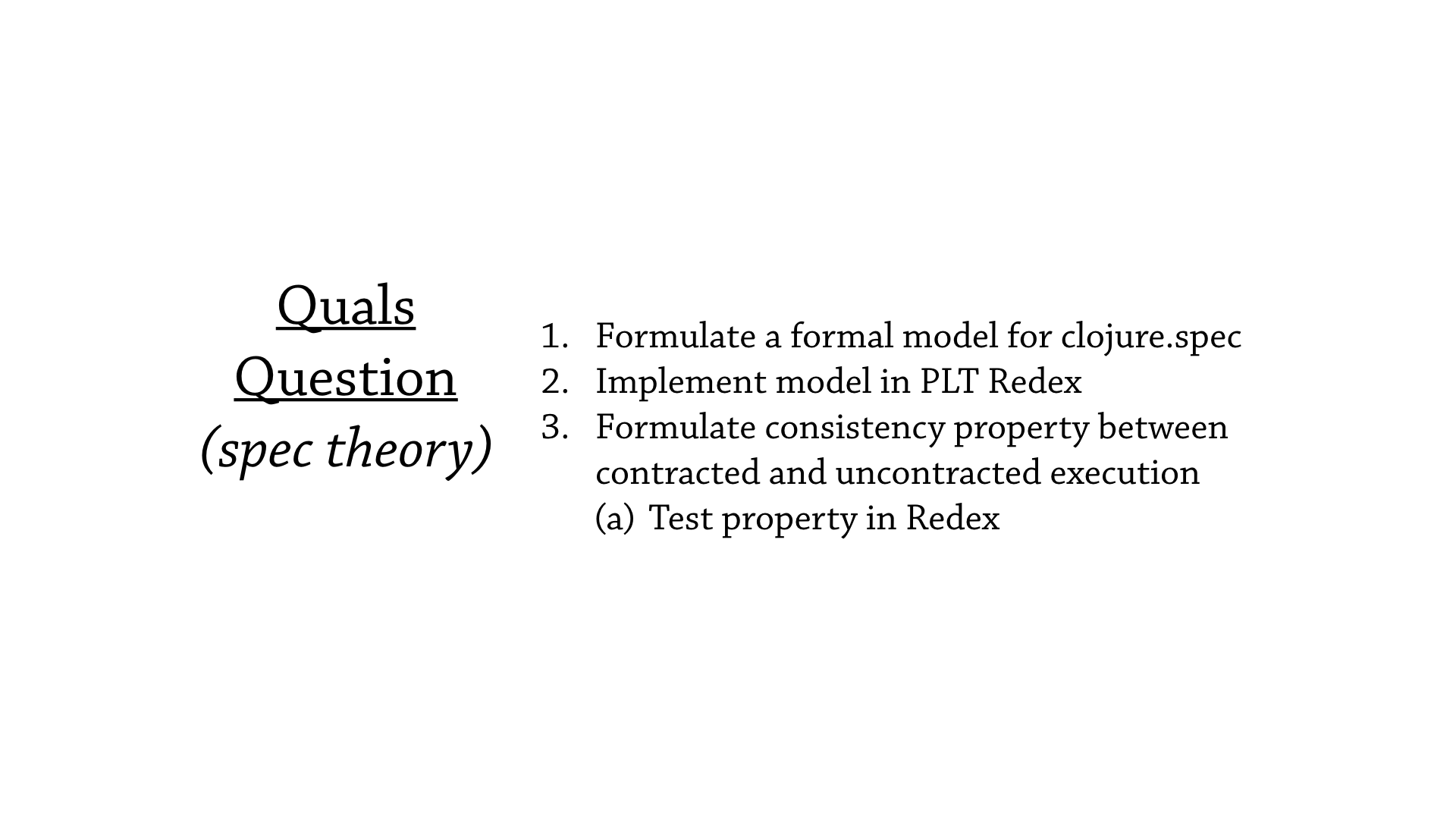

So the relevant quals question here is about the theory of spec, and it asks to formulate a formal model for clojure.spec, and then implement that model in PLT Redex, and then formulate a consistency property between contracted and uncontracted execution, and then test that consistency property in Redex.

Ok, I was just talking about how annotations can be buggy, or perform unexpectedly. How is that possible?

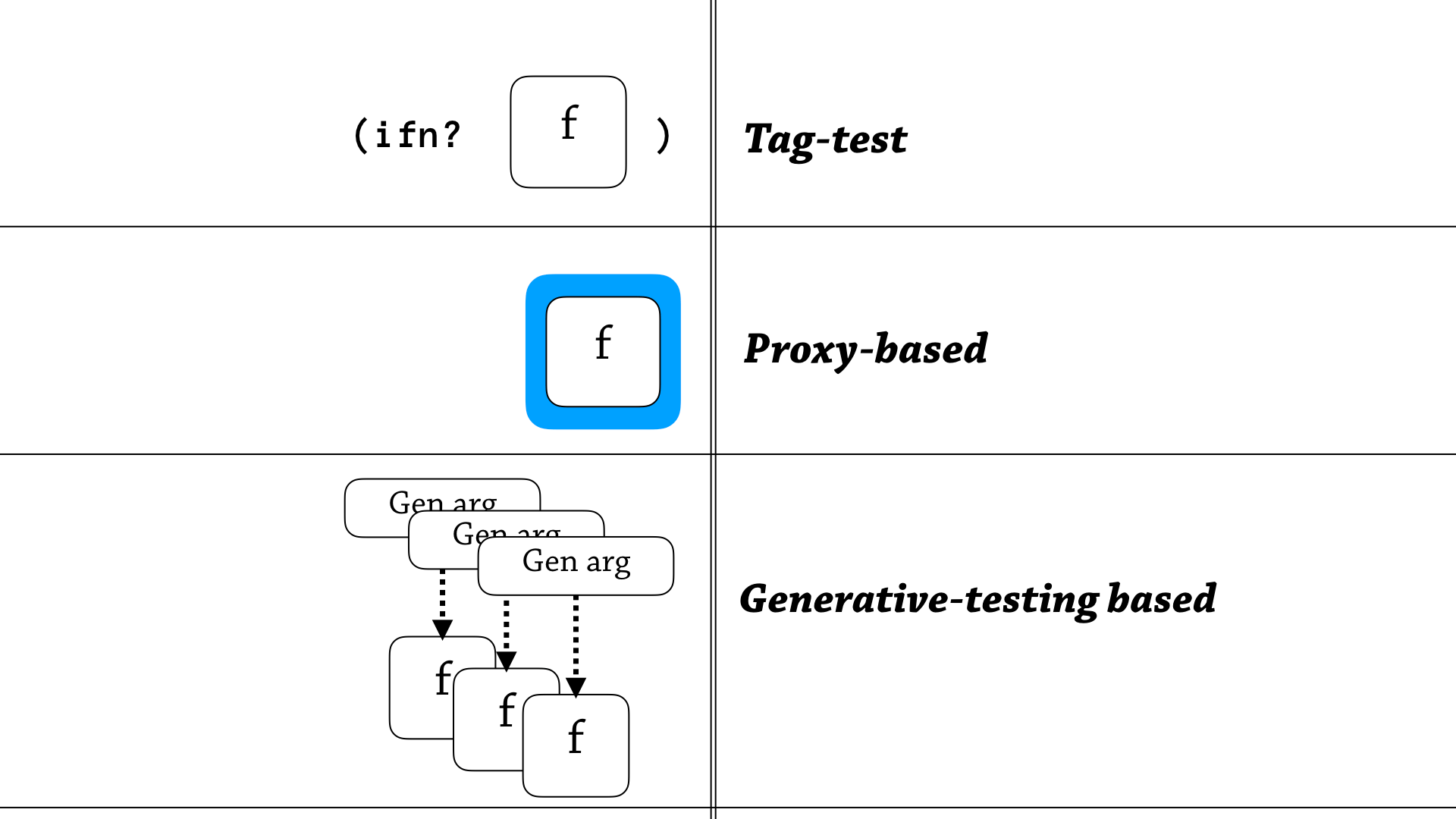

Well to start this story, I’m going to talk about some of clojure.spec’s different contract types, and it has three interesting function specs.

The first spec is just a flat test, just an instance test to see if an interface is implemented, and that’s just using the ifn? predicate.

The second semantics are proxy-based, so it’s traditional higher-order contracts—you wrap a function and wait for it to be called, and ensure something is of the correct shape before you pass it to the function, and then ensure it’s in the correct shape before you return.

But the third semantics are the novel kind that look a bit strange—it’s a generative testing based approach—and the idea is, to generatively test a function, use this particular annotation in clojure.spec, when it finds a function, it spot-checks the function using generated arguments, then lets the function go on it’s way. And the idea is that if you’ve done enough spot-checking, you should be sufficiently convinced that the function is actually of that particular shape.

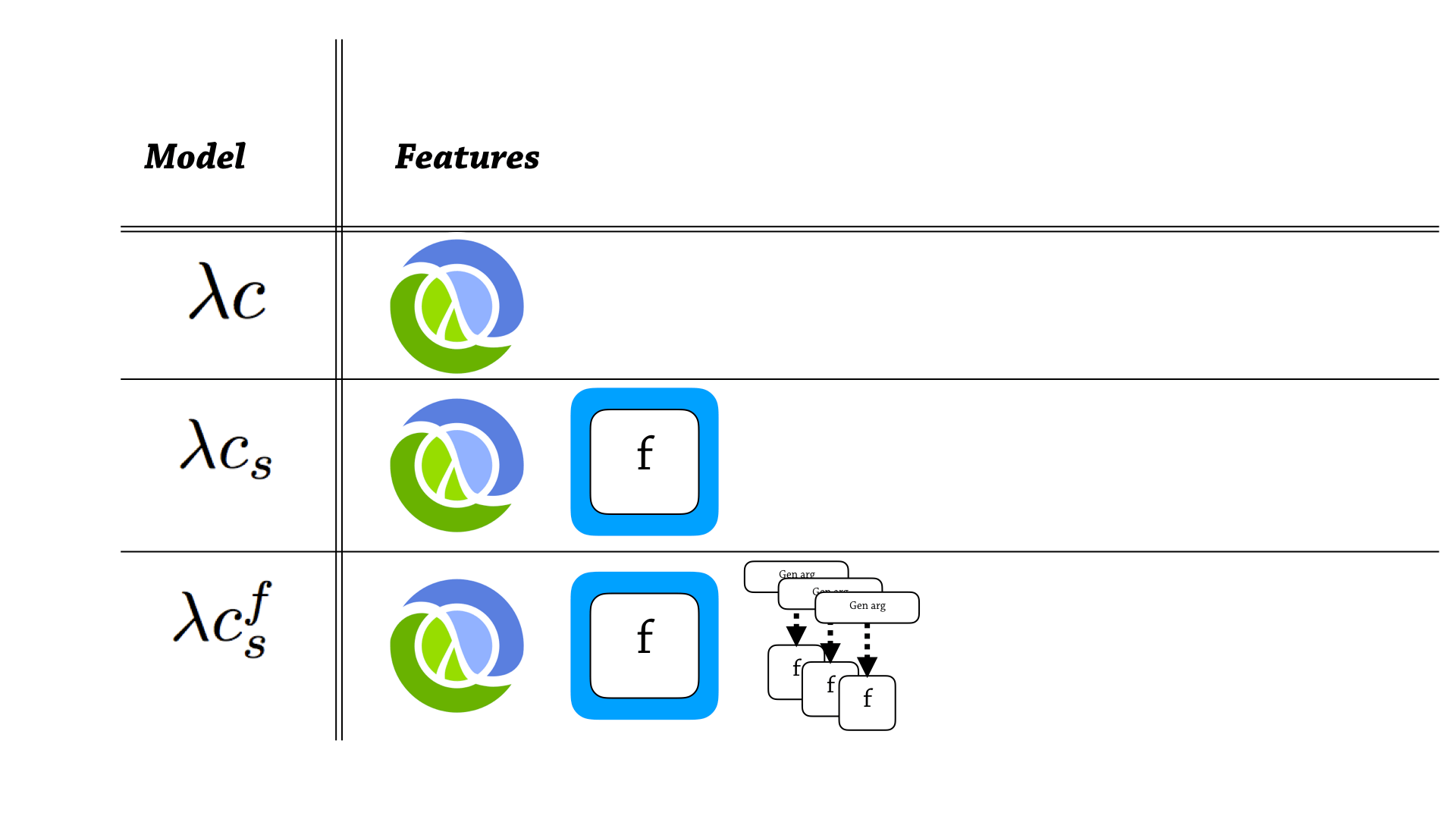

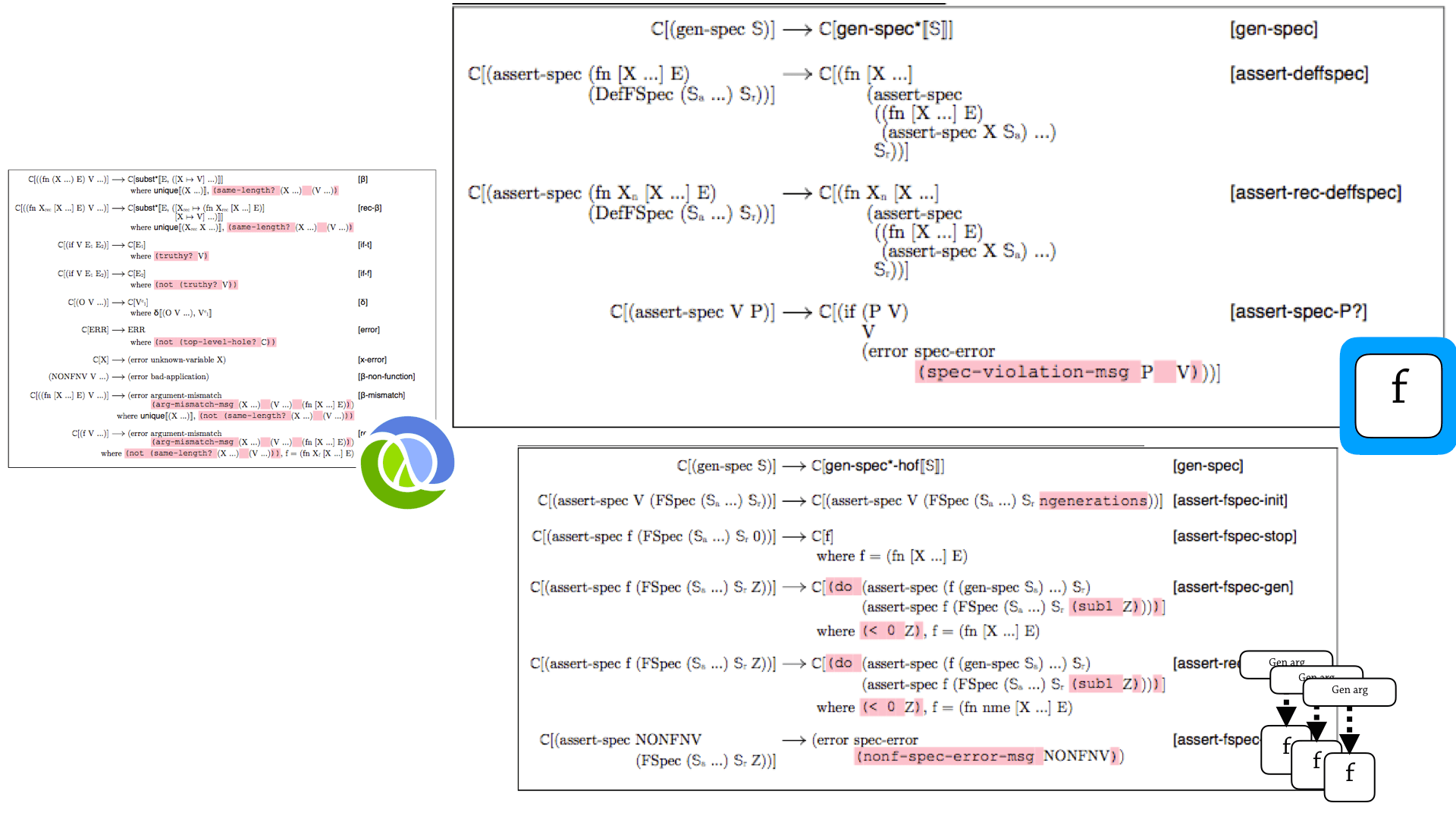

Ok. So I’ve used these function semantics to guide how I build this model of clojure.spec. So, it’s in three parts.

The first part just has vanilla Clojure—it’s basically a lambda calculus with hash maps, and conditionals, couple of other bells and whistles, but no contracts.

And then the second language has this base language of Clojure, but it also adds proxy based specs—function specs.

And then the third thing has Clojure, proxy-based specs, and also generative testing.

So now we can see, if we implement this in Redex, we can translate over this benefit of separating three languages.

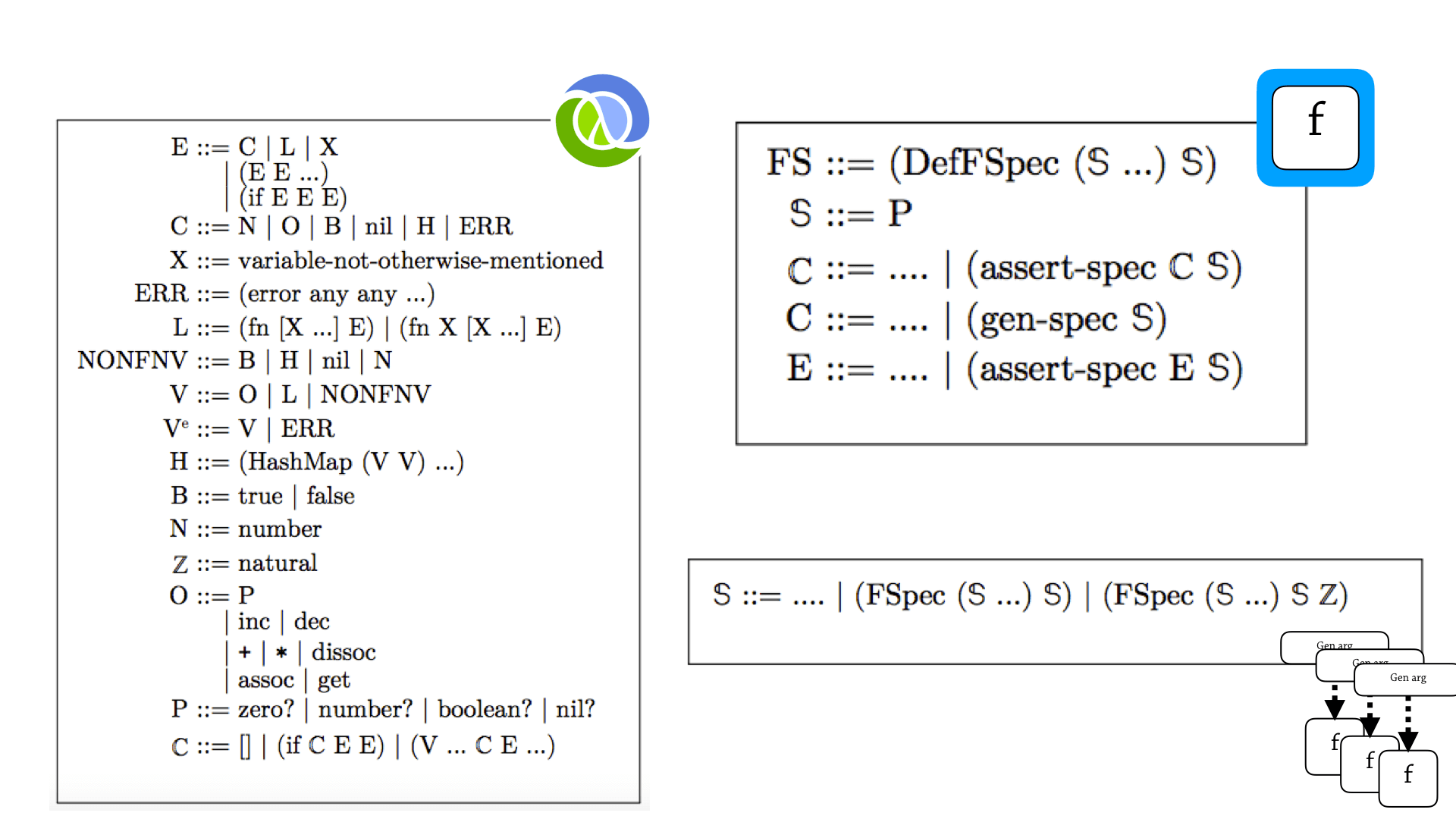

So, this is the actual grammar, as rendered by Redex. So you can see, there’s actually three languages here. On the left, there’s this base Clojure language that has a lot of the primitive forms, and then on the top-right we have the extensions for proxies—proxy-based function specs—and then on the bottom-right we have the grammar for generative-testing based functions.

And then there’s this similar story with the reduction rules. There’s a lot going on here, and we can go into detail if we need to, but you can see there’s a clean separation between the three languages.

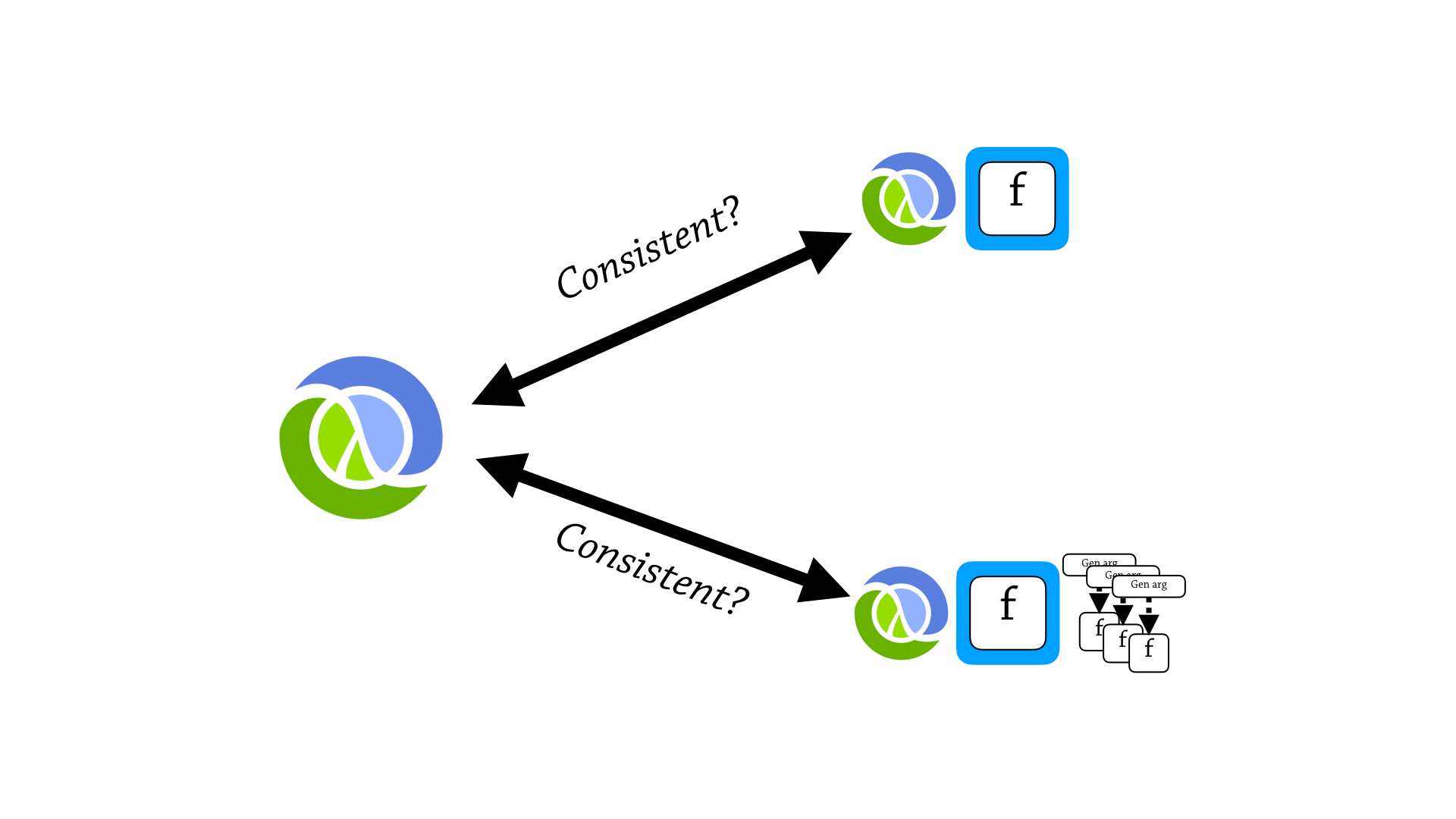

So now, we’re in a good place to test a consistency property between these languages—is vanilla Clojure, is it consistent with Clojure plus function proxies? Is it consistent with Clojure plus function proxies and generative testing functions?

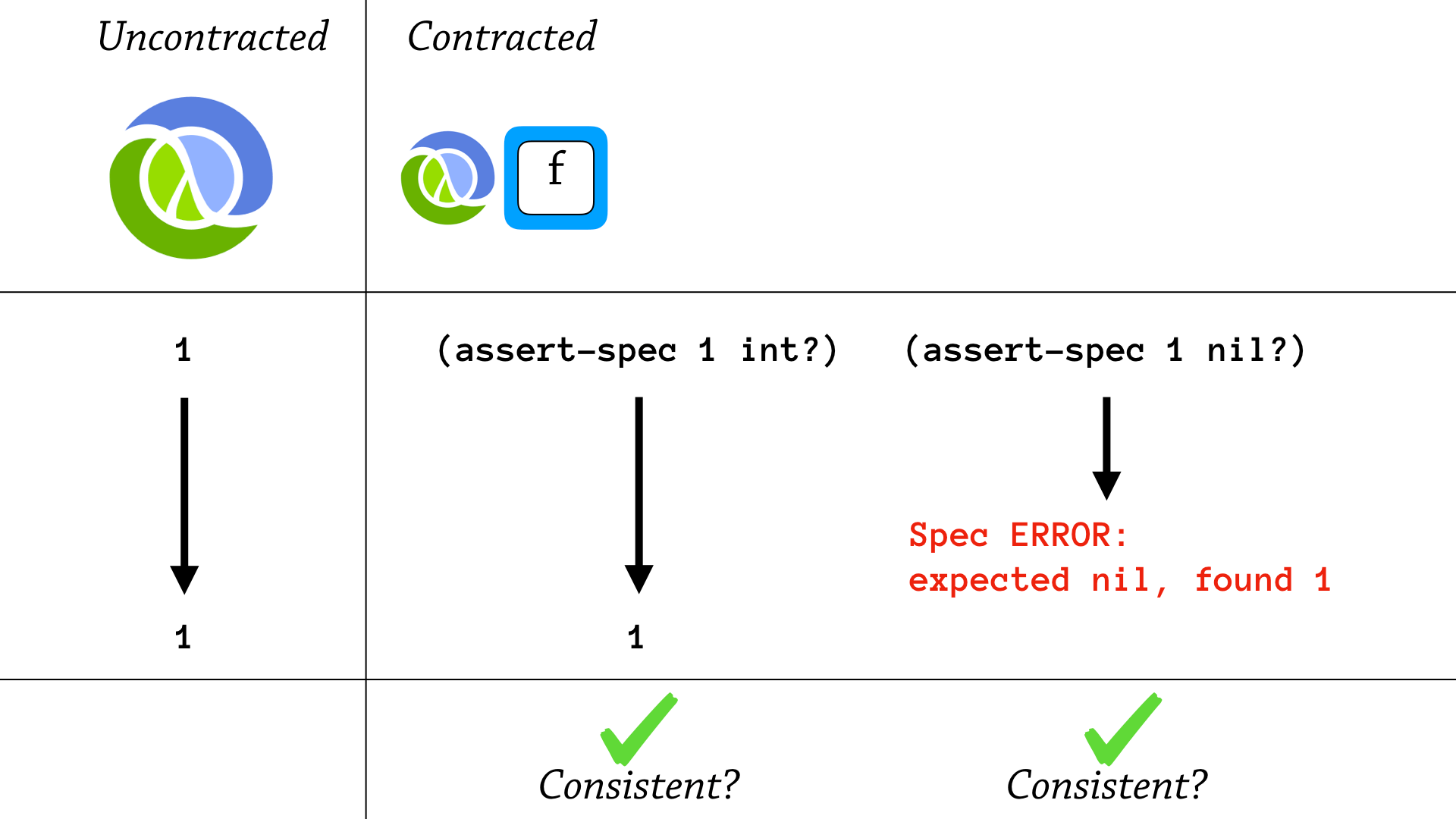

So, I haven’t defined what “consistent” means, and I’m going to try and define that using this particular slide.

So, there’s a spoiler alert here—is that function proxies don’t break the consistency property between Clojure—between contracted and uncontracted execution.

And, this slide demonstrates two of the ways it is consistent. So, let’s say on the left we have an execution that begins with the value—expression 1 and evaluates to a value, 1.

So, this is the uncontracted execution—in the middle we have a contracted execution, so we assert that 1 is int. And this is going to pass, and it’s just going to return 1. So this is consistent with the uncontracted execution, because the results are the same.

On the right, there is another contracted execution, but that results in a spec error—and I say that contracted executions are allowed to throw a spec error. Here it’s a test to see if 1 is nil, and it’s not and we get a spec error. And my consistency property says that you either have the same result, or you throw a spec error—and you’re still consistent.

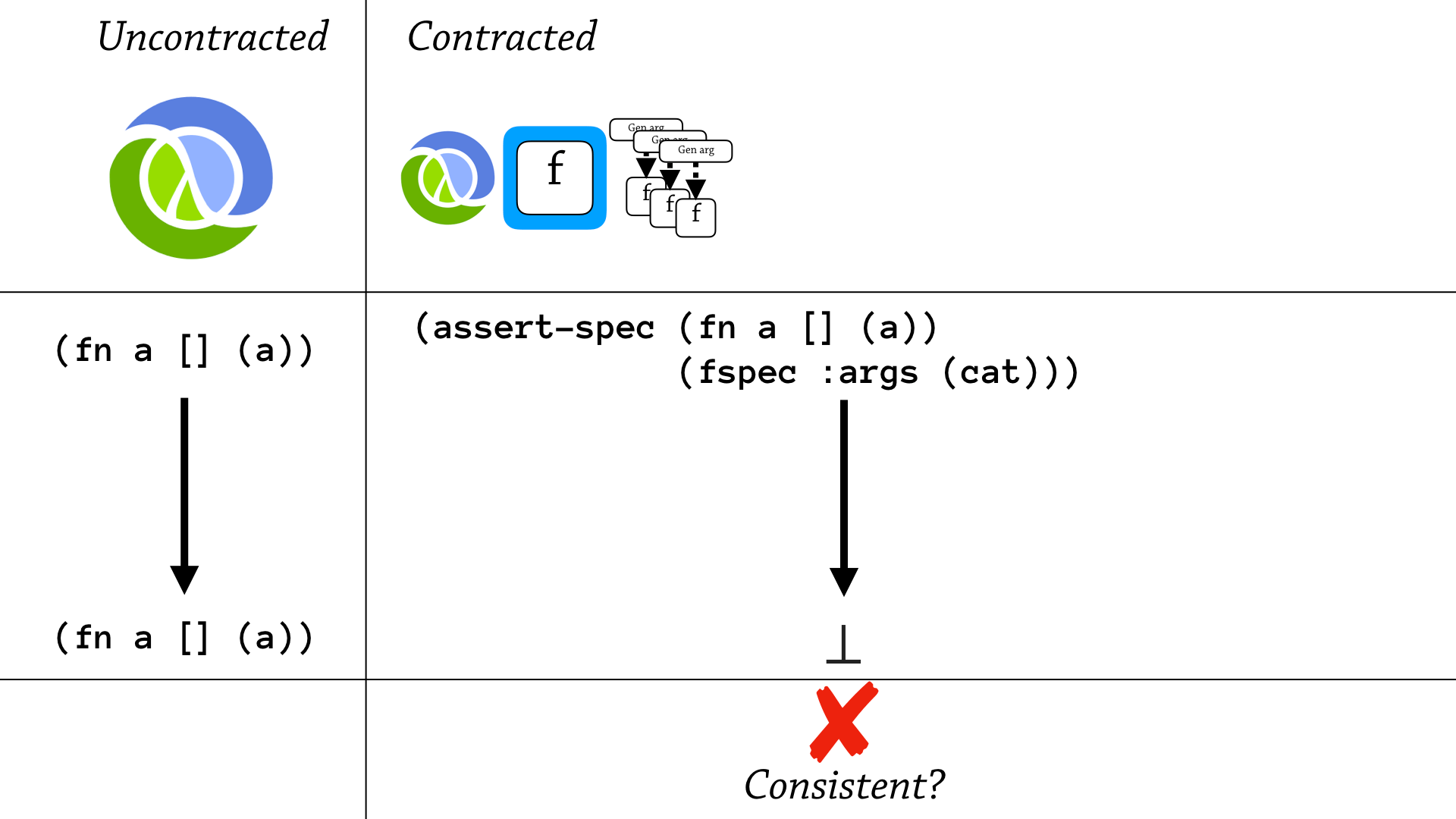

But, something weird happens when we add generative testing. And this is the simplest example that I can think of—is that you have, in uncontracted execution, you just evaluate a plain function that diverges, but you don’t call it, so the function returns.

But if you try and generatively test this execution, well you diverge, and you don’t get the same result—so it’s not consistent.

So function proxies are consistent, but generative testing function specs are not consistent with Clojure.

Alright, so let’s take a break for questions.

Ok, so the next part of my talk is about understanding the practice of the target language—how do people use this annotated language?

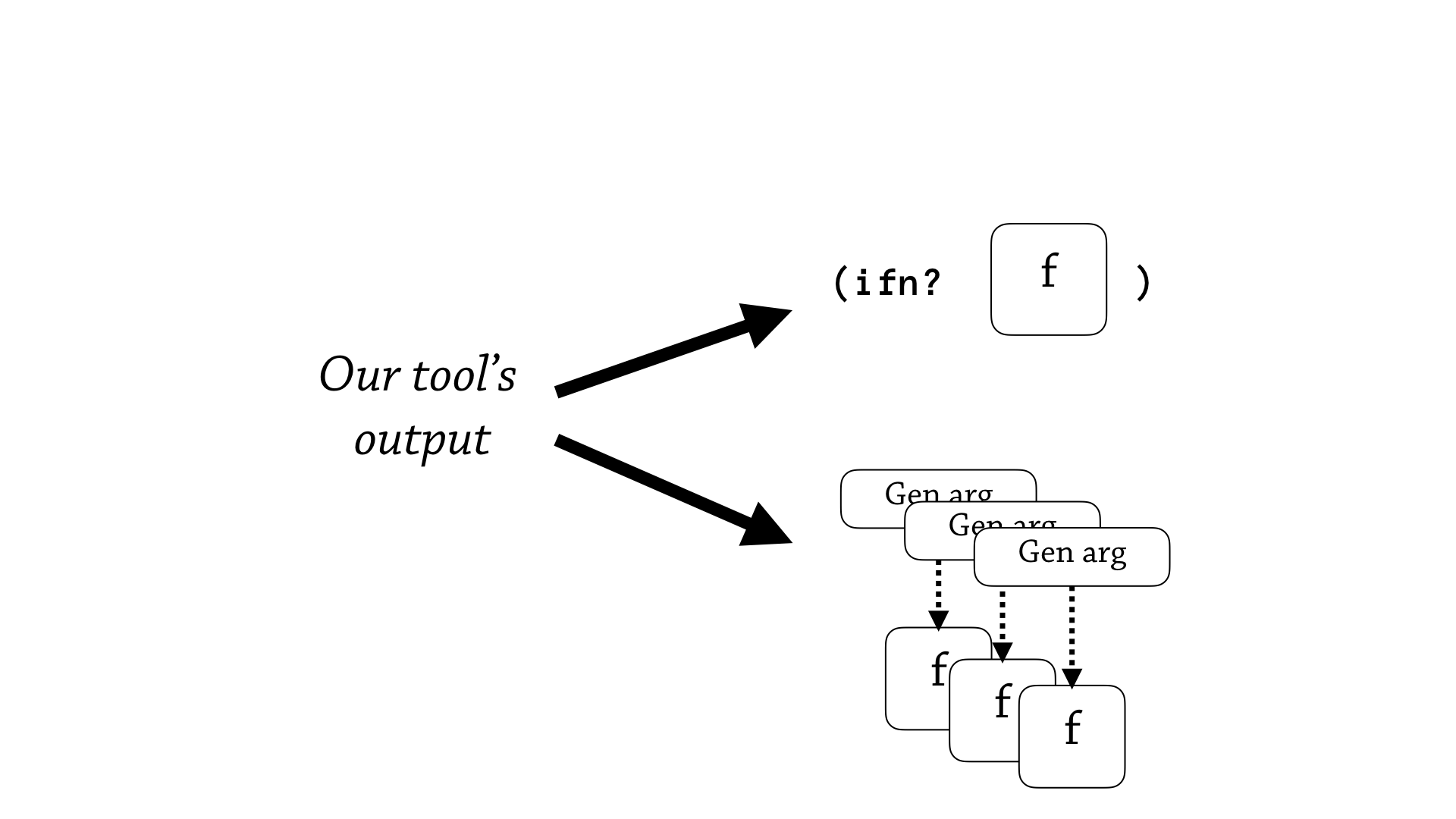

Ok, so there are two different ways that we can use our tool—that our tool’s output can be used.

One is that the programmer runs our tool, and then looks at the code, and says “Oh this is great!”, and just updates the code, like, pushes it to their repository. Another is that they reach for their “delete” key and start deleting or changing the annotation— and our tool is supposed to be a “productivity tool”, so if we can best predict what an average user would like out of their tool, then we are a more efficient productivity tool. That is why understanding the practice of the target language is important.

So here’s the quals question that is relevant here—and it’s about the practice of spec—and it asks to examine the usage of clojure.spec in real-world code bases, and then analyze the frequency and precision of higher-order function annotations.

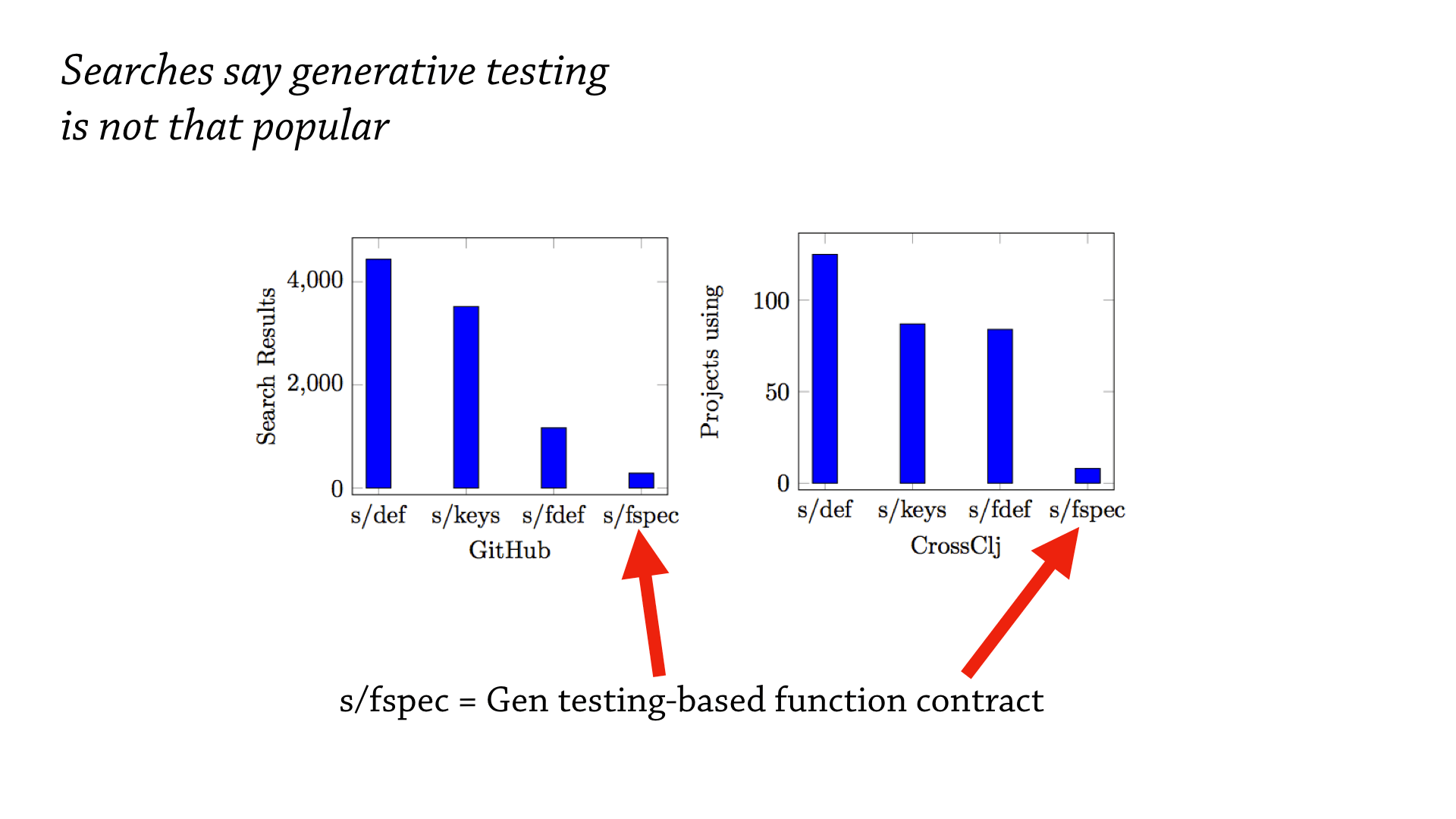

Ok, so I took to the internet and did some basic searches to start off, and one question I wanted to answer was “is anyone even using these function specs—these generative testing function specs?”.

And, you can see in clojure.spec, this thing is called an fspec. An fspec introduces a generative testing based function spec. And, it’s definitely not as popular as the most popular features of clojure.spec, it’s not even close, but people do use this—so this is encouraging.

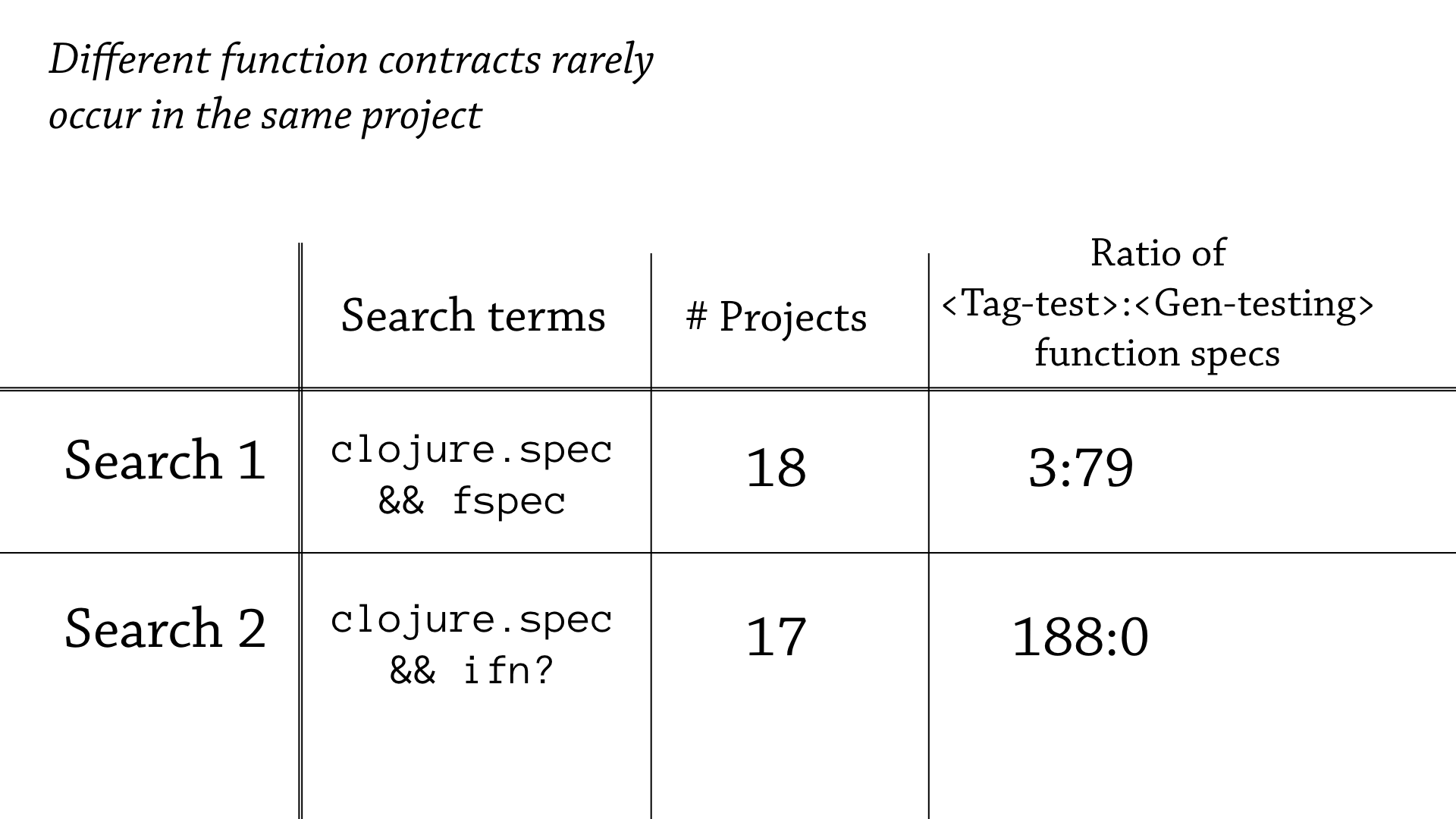

Ok, so I took this initial result and continued with this idea of searching, and I made a little experiment where I took two searches—one that biased generative testing, and one that biased flat contracts—and tried to compare how these two groups of projects used—the precision of these higher-order function annotations.

So in the first search, I’m searching for “fspec” and “clojure.spec”—hopefully I find projects that have generative testing in them—and I found 18 projects, and in those 18 projects I saw 3 tag tests and 79 generative testing functions.

In the second search, I’m searching for Clojure libraries that use clojure.spec, but also use this flat predicate of ifn?—hopefully I find some higher-order functions that are annotated with ifn?—and I in fact did find these projects, I found 17 of them, and they have 188 tag tests in them, but zero generative testing function specs.

So this is a very interesting divide, if you look at these two ratios on right, you can see that it’s very rare for a single project to mix these two semantics—to mix the flat function contracts with generative testing based function contracts.

So what does this tell us about our tool? Well, to me, at the very least it tells us that, we have to give more configuration options to our users.

Perhaps this user doesn’t like generative testing, or doesn’t understand it, or just likes the performance of ifn?, and would want our annotation generator to just spit out annotations that use the flat contract.

And then—but on the other hand, if a programmer likes the fine granularity of these fspec’s, and likes generative testing, they’d want to give a configuration option to say “I want more fspecs”.

So, that was the practice of spec, we’re going to break for questions.

Ok, so we’ve taken this knowledge of the theory and practice of clojure.spec and other target languages, and we’ve synthesized this knowledge into a tool that automatically generates annotations for these target languages—now let’s compare these to other tools.

So why would we want to compare our tool to other tools?

Well, the low hanging fruit here is we can at least test to see if our performance is reasonable compared to other tooling—and looking at other tools allows you to better understand the tradeoffs that we’ve made, and in turn, see if the tradeoffs other people have made are directly applicable to us.

So here’s the quals question that’s applicable here—it’s about a performance analysis, and it asks to compare the time and space complexity of our tool versus Daikon, and it asks: can we reuse some of Daikon’s optimizations, and also how expressive are Daikon’s annotations?

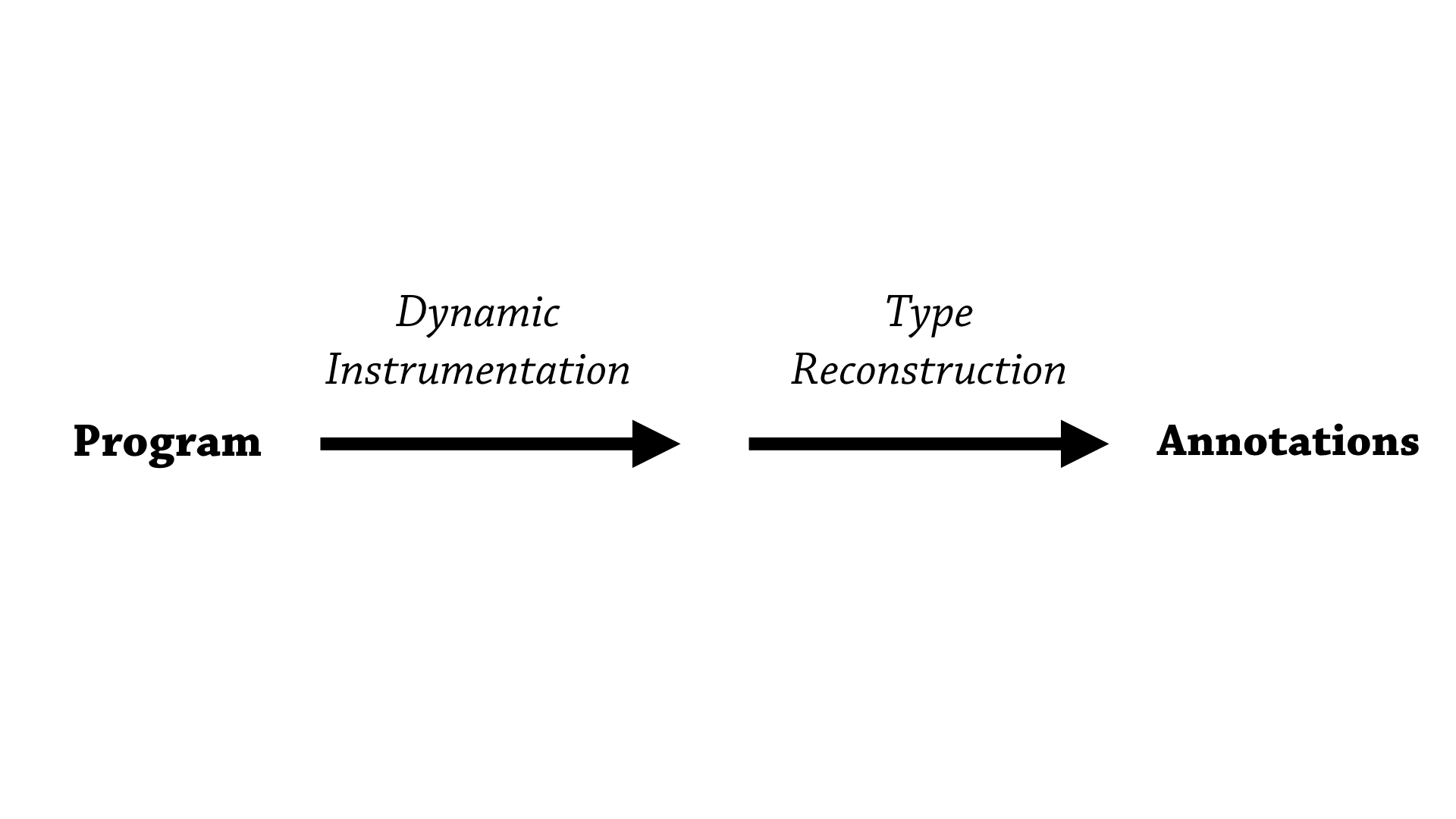

Ok, so both my tool—our tool—and Daikon have a very similar lifecycle when it comes to how it generates annotations.

So, when we start from the plain source program, we first go through a dynamic instrumentation phase. So we instrument the program, and then we let the program run, and we gather data about how the program is executed, and then we hold onto that data and once the program has finished running, we then pass that data to the type reconstruction algorithm that then munges that data and then spits out annotations.

So, turns out our two approaches to type reconstruction are almost opposite, and radically different, and it’s worth concentrating on how they are different and how a performance analysis between the two is difficult.

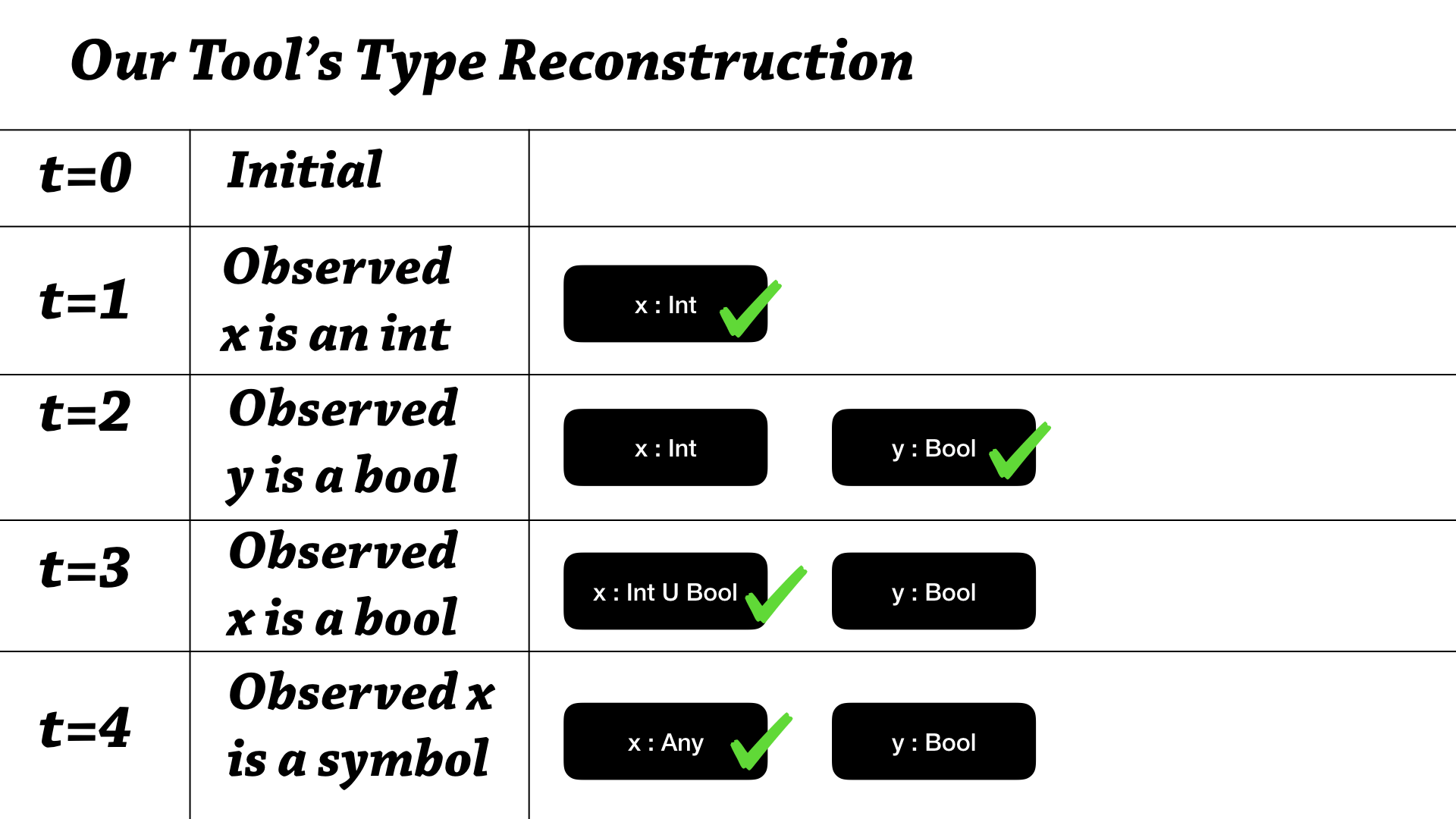

Ok, so in our tool, we have this lifecycle to the type reconstruction—let’s say there are 5 steps to the type reconstruction, and each step we’re processing a new piece of data, our observations about the running program.

So, at the initial point, our tools says “well, we don’t know anything about the resulting annotation, so we don’t need to store anything”. And then the next step, it’s found an assertion, an observation that x is an int, we say x as an int, and that means we can add that piece of information to our environment, and accumulate that piece of information, as x is an Int—and then, at the next step, we observe that y is a bool, and we can also add that piece of information.

So, here’s what happens when we observe that x is a bool. We actually——you can think of our tool as climbing up a subtyping lattice: every type is Bottom and then once we observe particular things, we can climb up—so x has gone from Bottom to Int, and the next step is going to be from Int to Int union Bool, it’s going to be more general. And, if we observe that x is a symbol, we might have a heuristic to compress these types—so instead of going to Int union Bool union Symbol, we’d go straight to Any—climb the lattice that way.

So, that’s how our tool works.

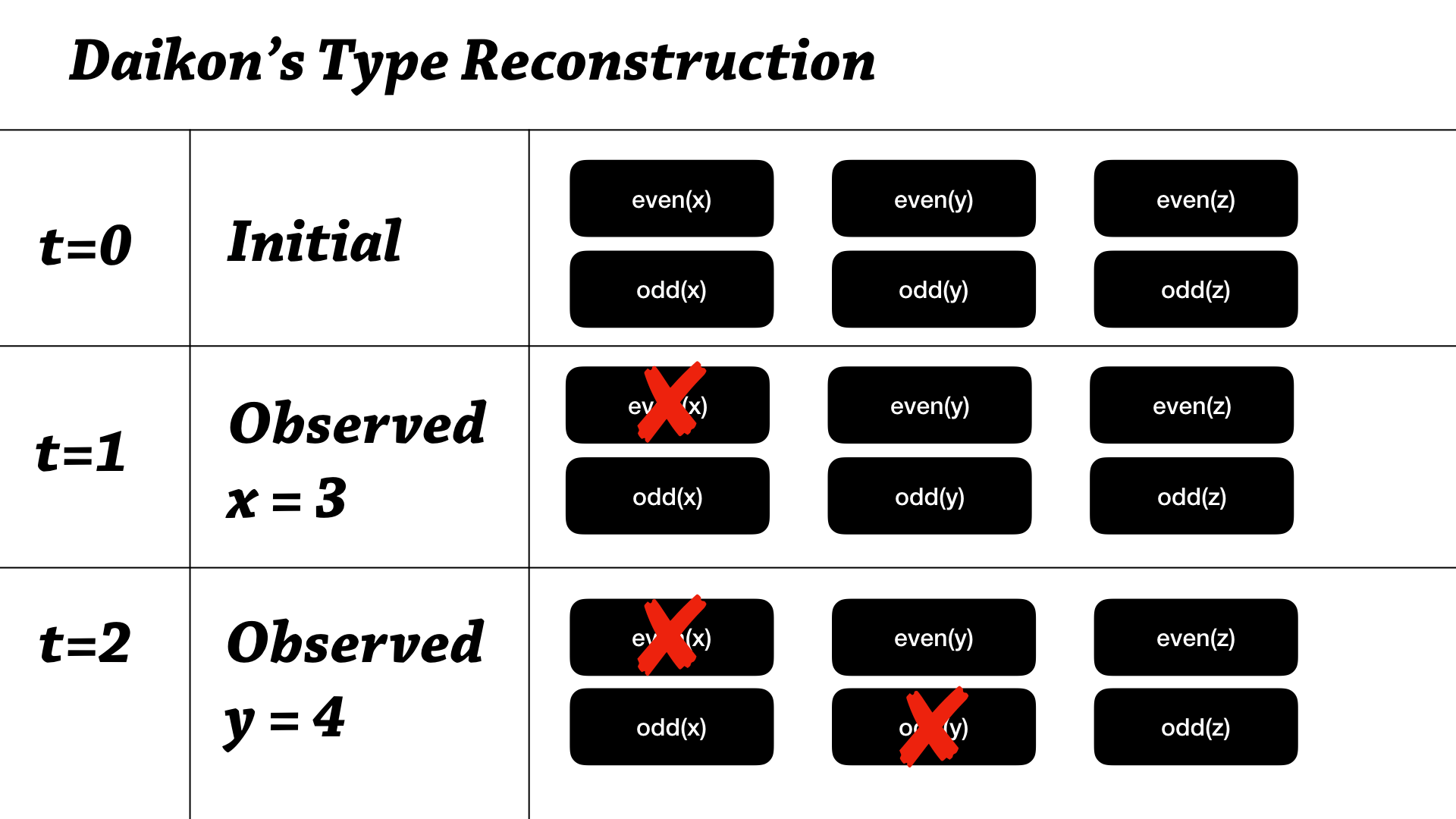

Daikon works pretty radically different. It has—and it’s for a variety of reasons—but here’s how it works.

So, at the initial point in time that type reconstruction algorithm starts, we actually assume “everything”—I guess I think about this as starting at the very top of the subtyping lattice, I’m not sure if that’s exactly the right way to think about, but that’s one way to think about it—that we assume that everything is possible. So, we assume x can be even, x can be odd, y is even, y is odd, z is even, z is odd— so all combinations of all the invariants and all the variables. As you can see, the space complexity and the initial space complexity are the same—you can only erase invariants from here.

So what happens when we observe something? So say we’ve observed that x equals 3. Well, we’ve observed x cannot be even, so let’s rule that out. And in the next step, we observe that y equals 4—we observe that y is even, so that means it can’t be odd, so let’s rule that out. And the idea is that we have enough samples early on to quickly whittle down the space usage of our environment.

So, space usage is Daikon’s number 1, almost number 1 priority when making optimizations.

Ok, and here is an optimization that Daikon has implemented that helps deal with the space complexity here.

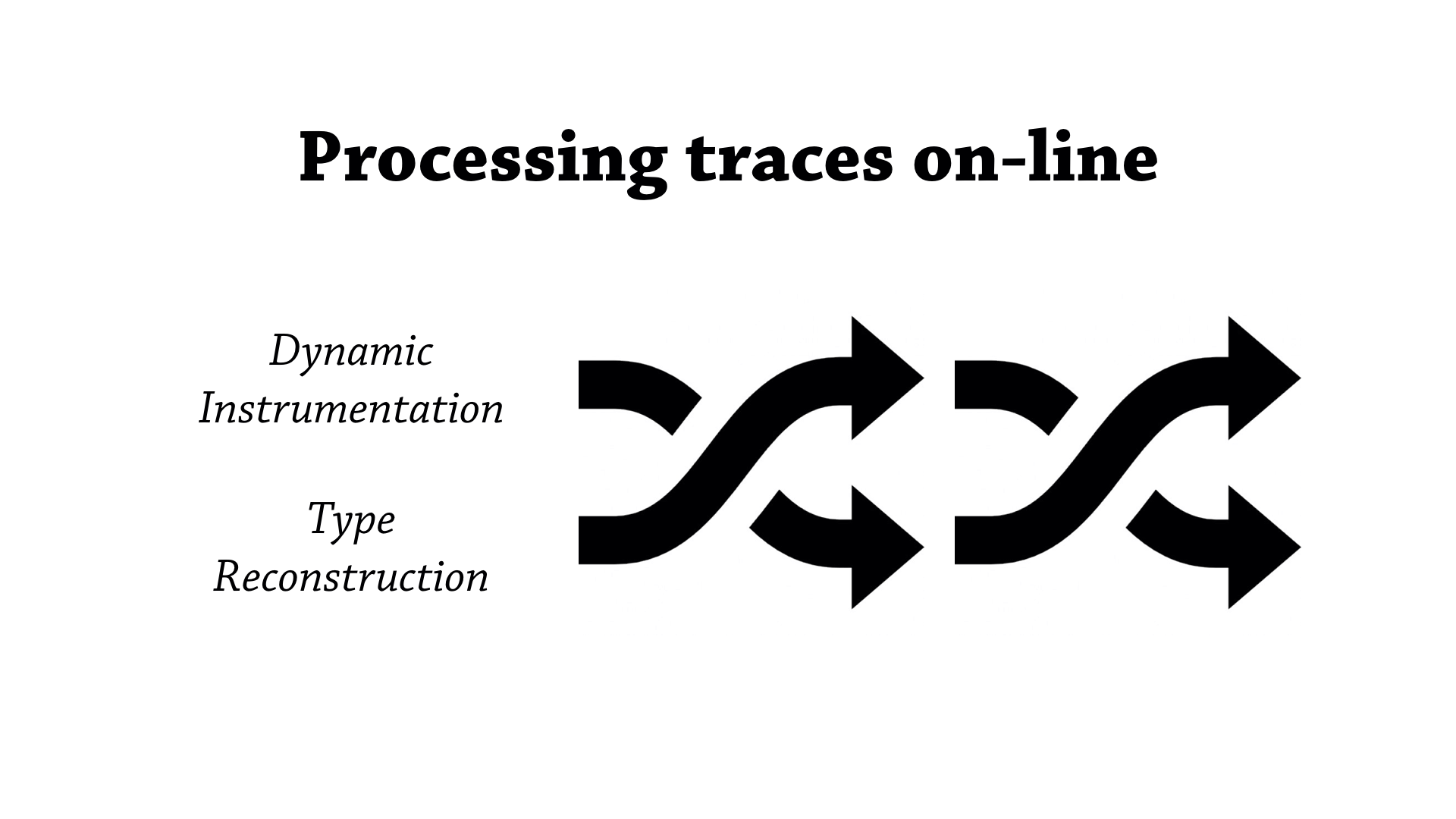

So, remember the dynamic instrumentation phase remembers a bag of data, and then passes that along to the type reconstruction phase—so imagine if you interleaved those two phases, you wouldn’t have to remember all that data. So that’s one optimization Daikon has: as soon as we—they call it a sample or a trace—as soon they gather an observation, one of these samples, they plug it straight into the type reconstruction algorithm and try and process it as eagerly as possible.

It’s an interesting question: is this applicable to our tool. Well, it certainly can we reused—and this is since both the tools have this idea of having a bag of constraints. For some reason—might be because we haven’t chosen large enough benchmarks—there hasn’t been really a need to apply this optimizations, and we haven’t noticed much issue—well at least not a space issue.

Ok, so let’s break for questions.

Ok. So to recap: I want to create effective tools to ease the transition to annotated target languages, and my approach so far has been to learn about, and understand the theory and practice of the target languages—and then once I synthesize that knowledge into a prototype tool, I can iterate on that prototype by comparing our tool to similar tools in the wild.

Thank you.